Mosaic and a Remembered Cliff Lift

Once upon a time, and scarily not-so-long ago, I was lucky enough to work somewhere that also happened to be a big Internet hub in Britain, and which — because of that — was one of the first places to get the Mosaic web-browser. World-changing stuff, but it just seemed curious at first. Quirky and cool, but not so much more than a toy. So what we did with it was what I suppose would be called ‘surfing’. Just following the Blue Brick Road from link to link, seeing where it might take us, finding out what the dimensions of this weird ‘World Wide Web’ thing were. If I’d sat up most of a night, I probably could have visited every web-site in existence at the time. That joke about ‘reaching the end of the web’ and needing to turn back wasn’t really a joke back then.

The web is so unutterably vast these days that I’m not sure we really ‘surf’ any more. We go to places we know. We search. We want what we want, and we want it now. I read somewhere that Google’s ‘I’m feeling lucky’ button is hardly ever used. We don’t want serendipity. We want relevance in a sea of babble. Which seems a shame, because once in a while a careless wander leads us somewhere that we might never otherwise have gone. A good measure of whether you’re ‘surfing’ or not is whether you can remember how the hell you got somewhere. If you’ve no earthly idea, you were probably surfing.

I haven’t a clue how I got to The first web mag about funiculars yesterday (and didn’t you just know that there’d be one?), but I happened upon something that made me both happy and sad, and was glad for the serendipity. It kind of filled a gap for me.

My childhood holidays were primarily spent at Scarborough, on the Yorkshire coast. A week or two during the long summer holidays from school, and my memories are all good. The place had — and still has — a magic that only a long childhood association with a place can create. My mother also knew the place from when she was a kid — it’s really a family haunt. On the other hand, my dad never quite seemed to connect so well with the place. Partly I think the climate wasn’t exactly what he associated with a relaxing holiday — he’s a sun-worshipper, and was much happier when we started going to more Mediterranean climes later on. But also partly because he didn’t catch the spirit of the place when he was a kid.

After our last family holiday there in 1984, we’d go back for a pilgrimage at least one day each summer — it’s about an hour-and-a-half’s drive across the wuthering North York Moors from where I grew up, but the radical bleakness of the landscape on the journey makes it seem much further. And we were all fond of saying that it would never change. Fundamentally that was true — the North Bay still genteel and sleepy, the South Bay still a babylon of penny arcades and Kiss Me Quick hats by the fish market on the harbour. The miniature railway still always ran around the parks and along the North Bay promenade. Enough of the touchstones of the place were there to make it feel like home.

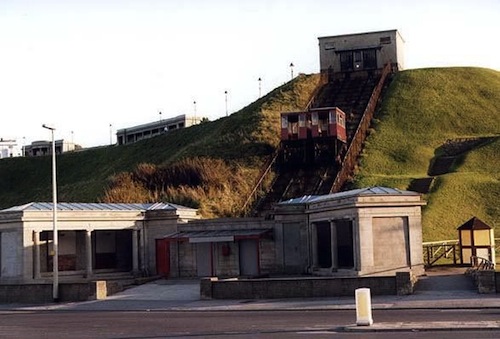

For some reason, there was a several-year gap in my pilgrimages in the ’90s, and then, when I finally got back in ’98, something of real significance had gone. Just vanished, the space it left behind landscaped so as to pretend it had never been there. It was this wonderful little monument to a more gentle age. The photographs you see there were taken in 1997, a few years after I’d last visited, and the year before I visited again. By the time I got there in ’98, the whole cliff lift had been packed up, sold and shipped off to a small coastal town in Cornwall, the hill-side resculptured (actually very very well, but still) to deny its history. The oversized stone shelter still remains at the bottom, but that’s all. The tracks are gone, as is the ticket office at the top. It’s all grassed over. Until yesterday I’d not seen the lift in this graveyard state.

We used to take this lift home from the beach every day. I’m sure that my sister and my dad must have been there some days, but in my memory it’s typically my mother and my brother and me. By the time of the holidays I remember best, in the late ’70s and early 80’s, my sister didn’t come with us — at least not for the whole trip. She was older and had another, more sophisticated world by then. My dad would usually leave the beach earlier than we did, and head back to the hotel for a nap before dinner.

So it was my mother, my brother, and me. We’d take the wandering path down the cliff-side from the hotel in the morning, bringing whatever supplies we might need for that day. The bulk of the day would be spent in a kind of British Seaside Zen, at the beach hut (Scarborough Council called them ‘bungalows’, and my parents called them ‘chalets’) that we rented from the Council each year. It’s the middle one of these, which was number 132, but has since been renumbered.

It was a wonderful location, feet from the beach, with a little cafe nearby in case we wanted some munchies. The huts themselves were self-sufficient, in a very austere British sort of way. Each one came with deck chairs, a small stove and sink, a little fold-out table. It was all we needed. We could sit and watch the weather doing whatever the weather was doing. Often raining, but not always. Impromptu football or cricket on the beach. Sandcastle-building. Much radio-listening and quiet reading. The obscure art of crisp-packet shrinking. And lots and lots of people-watching. The huts were raised from the wide promenade, so we could watch the world go by — especially on those hot summer days when it seemed that most of Yorkshire decamped to the beach. The hut to the left of ours (facing the sea) was occupied by a family from Leeds that was also there every year, so we formed a small community. The small patch of grass at the end of the row of huts was ours, for sun-bathing (in those moments of sun). Afternoon entertainment for my brother and me, and a couple of friends who were there each year, might involve a walk along to the delightfully cheesy fun-fair (now also gone, alas) which sat at the end of the prom, to while away a couple of sandy-feet-on-cool-concrete hours playing bingo for low-rent prizes, or trying to push foreign coins into arcade machines without being caught.

And then, at the end of the day we’d pack up the chairs and such, lock the hut, and head back along the now-quiet promenade towards the hotel. Only this time we wouldn’t dream of climbing that rambling path. This time we’d pay the small fee to travel in style, powered up the side of the cliff by electricity and iron engineering. Stepping out of the ticket office at the top of the hill, the beach would seem a thousand miles away, the path along the hill-top now a gentle stroll past the lonely stone shelters, decorated gaudily with playbills for whatever variety treat the Floral Hall (now also gone) was putting on that season.

That cliff lift journey was an important part of the ritual. It divided the beach from the hill-top, and it punctuated our day. A number of other cliff-lifts still operate in Scarborough’s South Bay, but the one that was part of my childhood is gone. It’s nice to see it, finally, in its final days, but I’d rather it was still where I remember it.

Update: A nice little piece in The Guardian, comparing and contrasting the delights (and histories) of Scarborough, on the north-east coast, and Blackpool, on the north-west coast. It includes this lovely line about Scarborough’s cliff lifts:

For some idea of the experience, imagine stepping into a cricket pavilion that suddenly begins to descend quite rapidly at an angle of 60 degrees.

I want to know about crisp packet shrinking. Surely it’s more than just eating crisps, right? Do you mean folding the packet up?

Janice: Very much neither of the above. It’s not just an obscure art, it’s also a dying art, and all for the cause of crisp-freshness. I’ll explain.

Before crisp packets were made of foil to keep the contents dewy-fresh, they were made of plastic, which behaved very interestingly when placed near to a heat-source. What we’d do is hold the empty packet – typically one of the smaller 35g bags that are the standard size in Britain – over the low heat of the stove. The heat would cause the plastic to contract quite startlingly, and with care to make sure that the heat was applied evenly, what you’d end up with was an exact miniature of the packet, perhaps an inch square, that was now hard and dense, and could be used as a badge, or a keyring, or whatever.

Of course, this doesn’t work with the foil packets. Having said that, the problem has been addressed elsewhere.

Interesting. It would never have occurred to me to iron my crisp wrappers. The cleverest thing I learned to do with an iron was to make grilled cheese sandwiches in college (in the stone age before microwaves, of course).